'It came out of nowhere':

Xylazine makes Vermont street drugs more dangerous and deadly

Dan D’Ambosio

September 8, 2023

Jeannie Morrill pulls back a bandage on her ankle, revealing an ugly wound, two tear-drop-shaped pockets of blood burrowing into her skin. She has another festering on her arm, and on her hip, she has a deep scar from the worst wound of all.

"This put me in the hospital," Morrill says. "It tunneled five and a half inches down and four and a half inches over. I almost lost my leg over it."

Morrill, 41, is addicted to heroin, but none of these wounds are at injection sites on her body. Instead they are caused by xylazine, a large animal tranquilizer being mixed into Burlington's illicit drug supply, along with fentanyl and other substances. Morrill had no idea at first she was injecting the drug along with heroin.

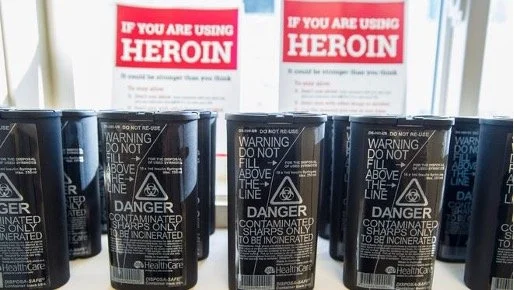

"The drug supply has gotten more dangerous, more deadly, more potent," said Erin O'Keefe, who runs the Howard Center Safe Recovery program. "People who use drugs have less clarity about what they're even using. You think somebody who wants heroin goes and buys heroin. But really someone who goes and buys heroin buys something that probably has no heroin in it, but is likely some mixture of fentanyl, unknown other substances and then maybe xylazine."

Xylazine, also known as tranq, has deepened Vermont's already daunting drug crisis, causing flesh-eating wounds like Morrill's, and putting people into a comatose state that Morrill compares to zombies. Dealing with xylazine has ratcheted up the stress on a health care system that's already straining from the pressure of rising drug overdoses.

A report released by the Vermont Department of Health in April showed a 10% increase in opioid-related fatal overdoses from 217 deaths in 2021 to 239 deaths in 2022. There were 158 opioid-related overdose deaths in 2020. Xylazine was involved in 28% of fatal opioid overdoses in 2022, up from 13% in 2021, more than doubling.

To make matters worse, xylazine does not respond to naloxone, the drug doctors and first responders rely on to resuscitate those who have overdosed on opioids. Xylazine is not an opioid, and there is currently no antidote available.

Bill from Sen. Welch would improve drug detection technologies

Sen. Peter Welch, D-Vermont, co-introduced a bill with Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, aimed at developing an antidote, and directing the National Institute of Standards and Technology to develop new tests to detect the drug in patients. Both Welch and Cruz serve on the Senate's Commerce Committee. Cruz is the ranking member of the committee.

"Xylazine is now implicated in many of our overdose deaths," Welch said. "(The TRANQ Research Act) would do a number of things. It's going to get some research done about what this drug can do and form partnerships to come up with an antidote. One of the big challenges is not being able to test for this drug in a person's system for immediate intervention."

TRANQ stands for "Testing Rapid Analysis and Narcotic Quality."

While there are currently test strips available to check for the presence of xylazine and fentanyl, Welch's bill directs the NSIT to develop better and faster ways to detect and analyze the drugs, as well as other novel synthetic opioids. The current test strips only determine the presence or absence of a drug; they do not measure how much of the substance, whether fentanyl or xylazine, is present.

Such a measurement requires spectrometer technology to provide chemical breakdowns, a technology that is not portable. Personal use spectrometers are still being developed and researched. Welch's bill would invest in that research and provide funding to develop this technology into a rapid, point-of-use tool that goes beyond test strips.

"At its core the bill funds research into better harm reduction technologies, so we can give folks more tools to protect themselves from an ever-changing drug landscape," Welch said.

As of this writing, the TRANQ Research Act had passed both chambers of Congress. The Senate amended the House-passed version, and Welch is waiting on the House to advance the Senate-passed version. Once that happens, the bill will go to President Joe Biden's desk for his signature, making it a law.

Whispers of xylazine give way to an aggressive assault

Dr. Daniel Wolfson began hearing about xylazine long before it showed up in the emergency department at the University of Vermont Medical Center, where he has taken care of patients for the past 20 years.

"We started hearing whispers of it five years ago on a clinical basis," Wolfson said. "Then it's really only been in the last couple of years that it's actually been impacting us. When it did start it came out of nowhere, very aggressively. It ramped up really fast."

From Wolfson's perspective, the skin wounds like Morrill's are one of the most horrifying aspects of xylazine.

"Xylazine causes small vessel vasal constriction, so it inhibits the blood supply to your skin, not just where you're injecting it, but anywhere in your body," Wolfson said. "So people have been coming in with these horrible − and I mean horrible − necrotic disfiguring wounds. You couldn't even imagine how bad they look, and they're on their face, their legs, their arms. It's not just where they inject."

Worse, the wounds often become "super infected," he said, turning into "deep, necrotic ulcers."

"I've never seen wounds like that before," Wolfson said. "Patients have been in the hospital for weeks and months with some of these wounds. Some require plastic surgery and multiple skin grafts. They're awful."

When dealing with an overdose patient, Wolfson and his colleagues in the emergency department still have to administer naloxone to counteract opioids, but with xylazine in the picture, they also have to be ready to give immediate respiratory and cardiovascular support if a patient doesn't wake up right away. Sometimes CPR is required.

"They don't always go into cardiac arrest, but a certain percentage do," Wolfson said.

As a result of all of these complications, overdose patients are spending up to 24 hours in the emergency department.

"They used to come in, give them the naloxone, they'd wake up and want to leave," Wolfson said. "That still sometimes happens but more and more we're seeing these episodes of prolonged sedation that don't respond to naloxone. You have to do supportive care. That's a big change."

Fear of withdrawal can override desire to avoid xylazine

For those unwittingly using xylazine, said Jess Kirby, director of client services at Vermonters for Criminal Justice Reform, many, like Morrill, are not liking its effects. Kirby, who is in long-term recovery from opioid use disorder, said she has a "trusting relationship" with her clients, who talk to her openly about xylazine, revealing its cruel ironies.

"They're like, 'No why would I like it better? I'm completely gone, asleep and then I wake up in withdrawal,'" Kirby said. "If you're someone who has opioid use disorder, and you're going to have withdrawal if you don't use opioids, and the only opioids you can access have xylazine, even if you don't want the xylazine you're going to use that because you're physically dependent on it, and you're trying to avoid withdrawal."

Morrill said she has learned which bags of heroin to avoid.

"I'm not going to intentionally put something in my body that's going to put holes all over me," she said.

A further complication, according to Kirby, is the problematic relationship many addicted people have with the medical community.

"People have major concerns about judgment and stigma and being treated poorly, and it happens," Kirby said.

Kirby remembers overhearing a nurse and doctor discussing her case after she had told them she was going into a treatment program. She was excited, and determined to succeed.

"What do I hear him say behind my back?" Kirby said. "'They're always back here in a couple of weeks anyway. Just give her seven days of whatever.' You hear the whispers and little things people say."

Someone you can trust is the key to recovery

Kirby struggled with substance abuse disorder for more than a decade before she found someone she could trust, and who believed in her − Tom Dalton, executive director of Vermonters for Criminal Justice Reform, now her co-worker and colleague.

"He was the person I came to when I was doing well, but also when I was not doing well," Kirby said. "The most important thing is having somebody that you can go to, that you trust. The relationship wasn't contingent on a desire for recovery. The important part is that you're cared about with whatever's going on."

Dalton said Vermonters for Criminal Justice Reform began in 2013 as an advocacy organization focused on criminal justice reform, but was soon drawn into providing concrete help and support for "justice-involved people with substance use disorder."

"System change is sometimes slow and incremental and takes time, so being able to help people in concrete ways every day is very rewarding and a good balance for us," Dalton said.

Working directly with addicted people also informs VCJR's advocacy work. In the last year the organization has worked with more than 150 people.

"Seventy-nine percent of the people we're working with tested positive for xylazine," Kirby said. "That's how big the problem is, and if we didn't have this direct service program we wouldn't be able to say that."

'We need a regulated, safer drug supply'

Before he became VCJR's executive director six years ago, Dalton founded the Howard Center Safe Recovery program in 2001, providing comprehensive care and counseling for people with substance use disorders. After so many years helping those battling with drug addiction, Dalton is clear on what he believes needs to be done about drugs. It's the same thing that has been done about alcohol and cannabis, he said. Legalize it and regulate the supply.

"We had alcohol prohibition and a lot of people were dying of alcohol poisoning because we had a dangerous, unregulated poisoned alcohol supply," Dalton said. "So instead we legalized it and we regulated it and so people have access to safer alcohol. There are still risks with alcohol, but we have safer versions. With cannabis we made it legal and we now have this whole apparatus in Vermont where the cannabis has to be tested for dangerous chemicals and contaminants.

"So it's a logical model to follow when we have a really dangerous supply of opioids that we need to come up with a safer version for people. We need a regulated, safer drug supply."

A life hanging by a thread

Even if Dalton's dream of a safe drug supply somehow came true, it would be unlikely to help Jeannie Morrill. Morrill credits Jess Kirby with saving her life − by caring about her unconditionally − but it's a life hanging by a thread. In addition to xylazine-induced wounds, Morrill is battling a blood infection that is eating holes in the valves of her heart and in her spine. She was headed to UVM Medical Center with Kirby after her interview for treatment.

"They're hoping a lot of antibiotics will help it, but nothing's guaranteed," Morrill said. "I might have to have open heart surgery."

Morrill also has Stage 4 liver disease, a legacy of contracting Hepatitis C. She says she's not interested in receiving a transplant, her best shot at extending her life.

"I don't want one," Morrill said. "This fight is tiring. I'm tired, I'm defeated, I've seen enough."

Dealing with a hurt deep inside

Morrill was not always so hopeless. In 2006, she was raising her two young sons and her two younger brothers while taking criminal justice courses at Community College of Vermont.

"I wanted to be a lawyer," she said. "That was my dream."

But Morrill also had a boyfriend who beat her. She started taking pain pills to make the beatings hurt less, she said. In 2007, police raided her house and she lost her children.

"I found a needle full of heroin and a pipe full of cocaine and I just tried to die every day, because I didn't know how to live without the pitter patter of my kids' feet," Morrill said. "And then it's just been a vicious cycle since, because you get an addiction and you can't afford the addiction."

Morrill shoplifted and hustled drugs to support her habit.

"Once you're caught up in the law, you're in and out of incarceration, so it's hard to get the children back," she said. "You're dealing with the guilt and shame and blame of that every day, and you just try to bury that more and more with drugs."

Morrill lives on the streets. She is trying to spend fewer nights in City Hall Park.

"I try not to be there as much anymore because it's scary," she said. "There's more shootings, there's more fights, there's more craziness, people robbing people. I'm too sick for it. When I can I stay at a friend's or a relative's."

Learning for the first time that Morrill is not considering a liver transplant, Kirby offered to take her to an infectious disease appointment, just to learn what her options are. Morrill agreed to go.

"I hope that I could help a little bit and that this (interview) will make people look at addicts in a different light," Morrill said. "We're not wonderful people. We're not honest people. We've stolen. We've lied. We've manipulated. That's what addicts do, trying to survive. But when you go by and you see people with their head between their ankles, just know they got that way from a hurt deep inside."